Nguyen Huu Huan is one of the Boat People, braving the South China Sea himself during his own journey to freedom. He currently resides in Hamburg, Germany. Here is his incredible story aboard the humanitarian vessel Cap Anamur II.

I. “A Ship’s Name, and a Noble Undertaking”

Here I am again, in Singapore. With me are my memories of the four days I spent on the open seas before the Cap Anamur rescued us in September 1980, and of my three months living in the refugee camps. It’s only been a year since, and I return to this place with renewed purpose, and pride in my task: to accompany the Cap Anamur back into the South China Sea to search for and rescue the Vietnamese Boat People on their journeys to freedom. From that day, I became a recognized crew member of the Cap Anamur, a name that would go on to become a symbol of humanitarian efforts of the twentieth century.

The name Cap Anamur comes from a small port in Turkey which lies on the Mediterranean coast. They gave the ship a normal name with no meaning. But its noble undertaking has made it famous all over the world.

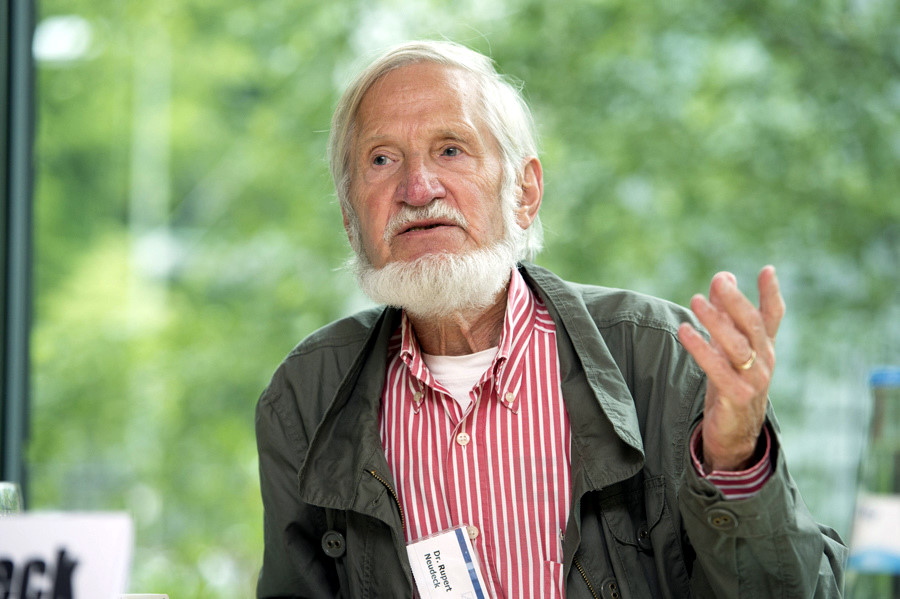

The CA Committee or “Committee for a Ship for Viet Nam” was founded by Dr. Rupert Neudeck in January, 1979. Later on, as its humanitarian mission expanded to other countries in Southeast Asia like Cambodia and Laos, it changed its name to Committee of German Rescue Doctors (1981). In 1982, when the Cap Anamur I was forced to return to Hamburg and end its mission, the committee became Committee Cap Anamur.

In the Beginning, the Cap Anamur was used as a floating hospital to provide medicare to over 35,000 Vietnamese Boat People in the refugee camps in Southeast Asia. All Committee members were unpaid volunteers working on site for at least 3 months. Its mandate was to help these people however we could, and the Committee had freedom in deciding who to help and how, without interference of a third party (i.e. governments). Monetary assistance to refugees was not allowed, and team members had to be present throughout the rescue period.

The Cap Anamur I performed its mission from July 1979 to May 1982; it made 29 total trips, rescuing 194 boats and 9,507 Boat People. On its last trip to Hamburg on July 26th, 1982, it brought back 258 Vietnamese Boat People.

II. “Witness our Journey to Freedom”

After a break of four years and endless lobbying, a second humanitarian ship, the Cap Anamur II came to life, registered as REGINE, but with the same noble mission as its predecessor. I had the privilege of returning with it to Singapore on a three month long mission, making three trips from March until June 1986, rescuing 18 boats and 888 Vietnamese Boat People.

During those trips, I lived the thrill of heading toward the direction of my homeland. I saw myself in the desperate people crammed in those tiny boats and I shared their fear and suffering. However, with a sense of pride, I recognized my contribution in the sea of human kindness and the chance to become a witness of our journey for freedom.

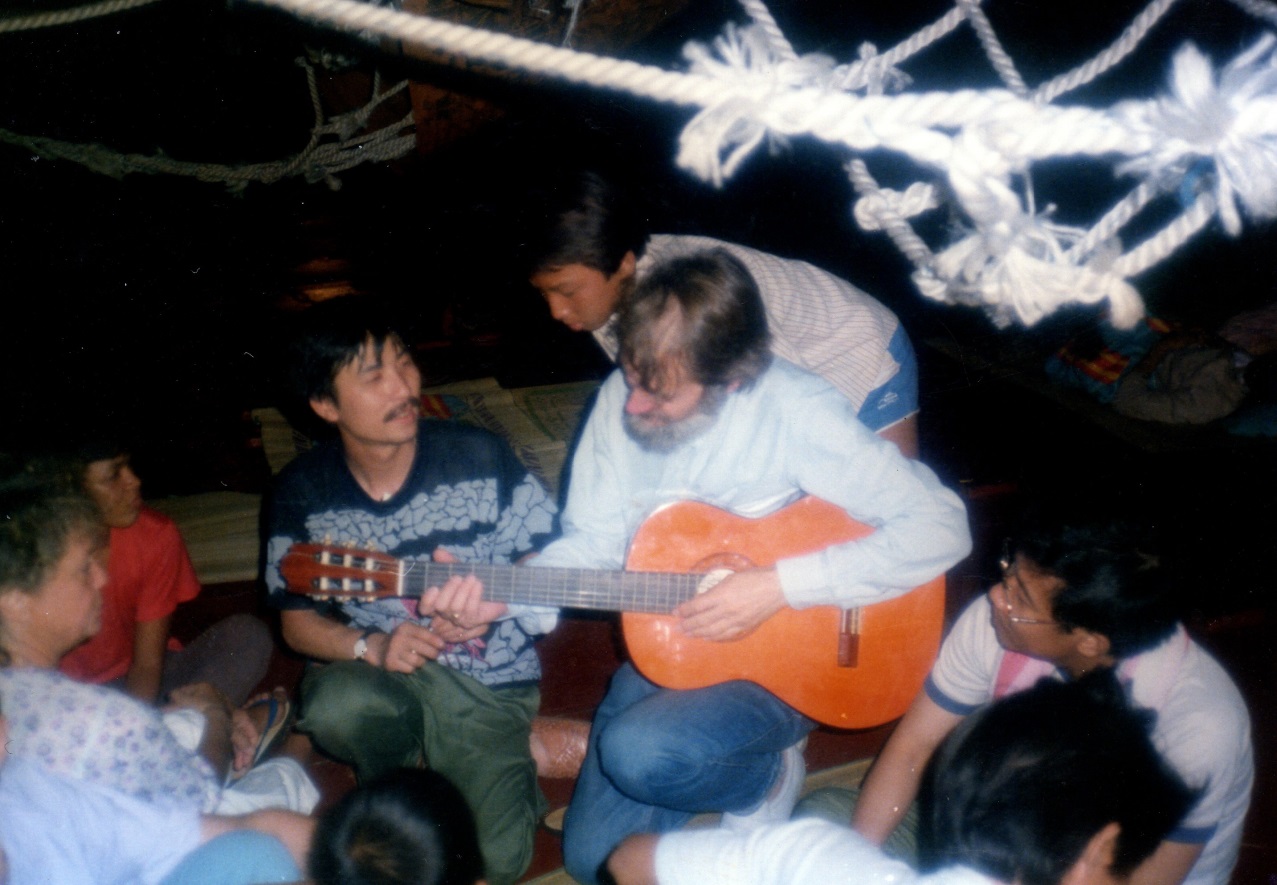

I can never forget those skinny, pale and fearful faces the moment they reached our ship. Vietnamese faces, oh so Vietnamese! The crew consisted of eight Germans, three of whom were former refugees of East Germany and Poland, crossing the Iron Curtain long ago. As such, they understood what we were going through, which gave me even more enthusiasm and confidence to be working alongside them.

The last trip of the Cap Anamur II on the South China Sea lasted five weeks. We rescued 8 more boats, and 358 Vietnamese Boat People, aged from 66 years to just 17 days. Some boats were on sea for 5 days, while some lucky ones were there for just 20 hours before rescue.

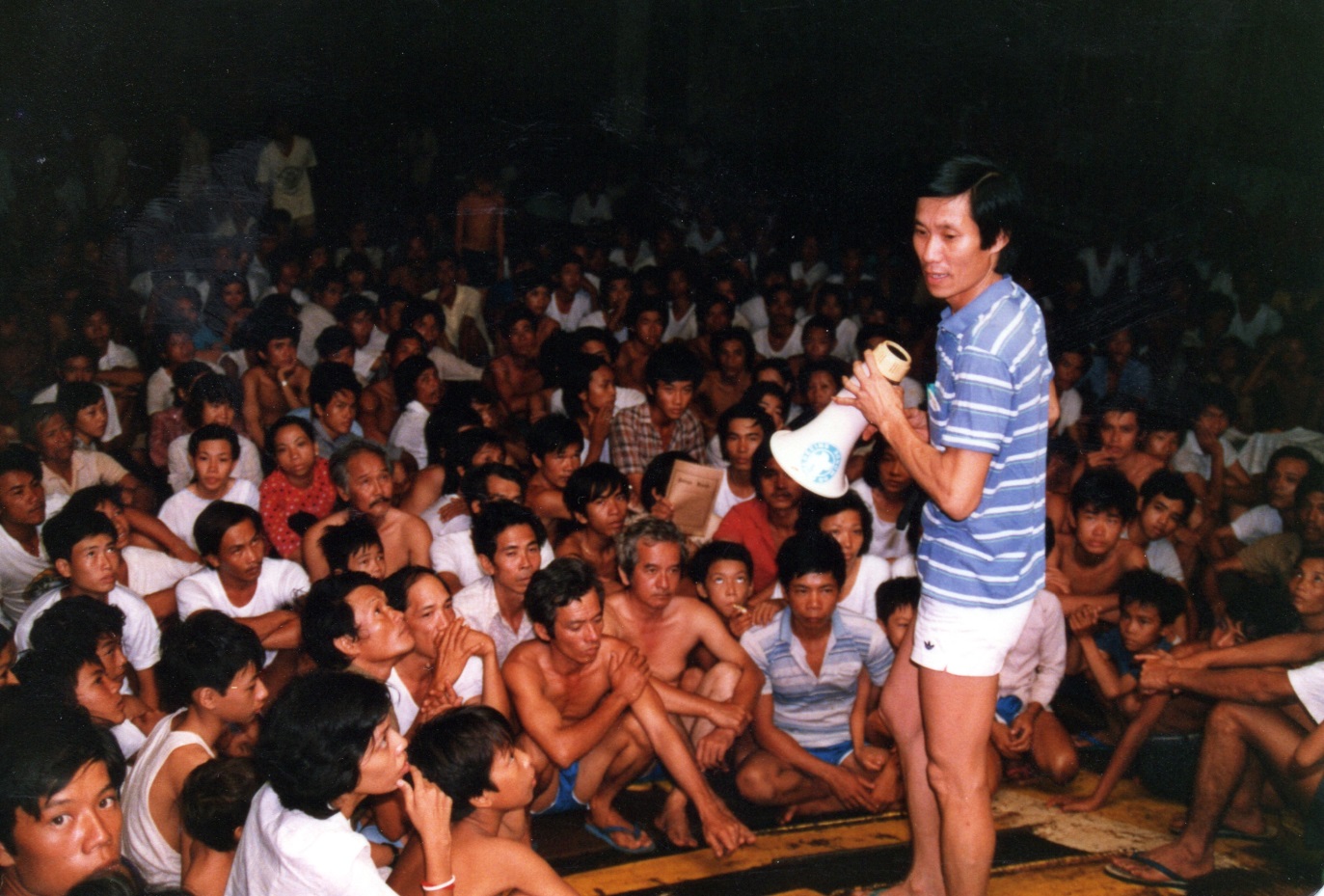

Recognizing a refugee boat was not an easy task. We had two search areas: Vũng Tàu and Cà Mâu, and all Committee and crew members took turns watching and scanning through binoculars. With so many fishing boats of different shapes and sizes from Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines, we could only rely on our experience to identify a refugee boat. As soon as we saw one, we would slow the ship down, me and a crew member would use a canoe to approach the boat. Once there, it was my responsibility to climb onto the boat to inspect it, to calm the refugees’ fear, and lead them onto the ship. All crew members were then mobilized to help them board the ship. The sick and injured were lifted up by cranes. Tears of joy flowed down the refugees’ faces.

On our last trip, we were fortunate enough to get the assistance of two members of the Boat People SOS Committee, originating from the US, Dương Phục and Nguyễn Tất Hiền. They helped us care for the 358 rescued Vietnamese (361 including us!) who had braved the open seas for days, facing cruel pirates and desperately searching for help. The 358 Vietnamese we saved were family to us: they shared the blood of our parents, siblings, and children.

III. “Quick Decisions”

We encouraged the 358 to act like proud Vietnamese and keep in high spirits in spite of the long and difficult period ahead of them before our arrival to Hamburg. To keep the busy and useful, each one was assigned a responsibility and belonged to a team: sanitation, cooking, search and rescue, translation, health services, entertainment (which even included lion dancing!)

While in the search area, we ran out of all food except rice. We quickly decided to buy fish from the fishing boats and use the wood of the refugee boats to burn as fuel. Teams to purchase and prepare fish and to chop the wood were formed immediately. It wasn’t easy for the refugees to watch their boats cut into pieces and burnt down; these boats were symbols of our country and the spirit of our people. Many tears were shed as the wooden planks burnt: tears of joy for the lucky few who survived, and tears of sorrow for the loved ones and the country left behind.

Buying fresh fish was not a simple task. First, the ship couldn’t stop too close to a boat. Second, the fishing boat had to travel alone and couldn’t be part of a float. We met a lot of fishermen from all parts of Vietnam, all very inquisitive about us. Some of them wanted to join our group while others we suspected others of being coast guards. However, once the fish was found and the prices agreed upon, we pulled it up in exchange for a basket up apples, a few packs of Marlboro cigarettes and the Vietnamese money collected from the Boat People which we dropped down to the fishermen. We all enjoyed the fresh fish.

One time, while stopping for a sale, two fishermen used ropes to climb up our ship and requested asylum. Who were they? What was their intention? What would happen if they went back to Vietnam? To reach a quick decision, I gave them a choice: they could all join us (there were eight of them in the boat in total) as refugees and sink their boat, or go back to the “paradise” all together. After a few minutes of consultation among themselves, they started the engine and left.

IV. “The Shortest Route, but a Long Journey Ahead”

While on our mission, we received the order to return to Singapore and to end all efforts starting July 1986. Dr. Neudeck explained that the decision was due to a lack of interest in receiving more refugees by Western countries including Germany, the refusal of the Philippines to accept the 358 refugees, the indifference of Canada which did not keep its promise to take in 100 people, the rejection of Australia and the silence of the US. Everyone on board was surprised, frustrated, and confused by the decisions of countries we saw as “free”, bastions and safe havens. The refugees saw their dream evaporate. 358 people lost hope and faith in reaching a Promised Land.

Nobody understood that we would rather die than live in oppression. A young man, feeling so hopeless, jumped to his death in the sea in Singapore, leaving behind a wife and two kids in Vietnam. We (Dương Phục, Nguyễn Tất Hiền and I) were shocked on receiving the news of his death. We had rescued him, but how many nations had condemned him to death in the events thereafter?

On July 25, 1986, Dr. Neufeld sent us his final decision: head back to Hamburg with the 357 passengers. The trip lasted 6 weeks, across the Indian Ocean, straight towards the south of Africa, crossing the Red Sea and the Suez Canal, hugging the cost of Spain and heading north. The shortest route from Singapore to Hamburg was 18,000 nautical miles, and our 357 braved the storms to reach their safe haven.

We had said goodbye to our friends Dương Phục and Nguyễn Tất Hiền when the ship docked in Singapore. Amidst tears, we thanked them for blowing hope and love into the refugees’ hearts, for capturing their portraits and words to show to the world what happened daily on the South China Sea. We promised to see each other again on Tư Do Avenue or Công Lý Street in Viet Nam, one of these days. Before we left, out of kindness, the Singaporeans gave us, sugar, rice, fruit, fish sauce, preserved and frozen meat and bags of clothing. And I was left to accompany the refugees on their long journey to Hamburg, a once in a lifetime journey.

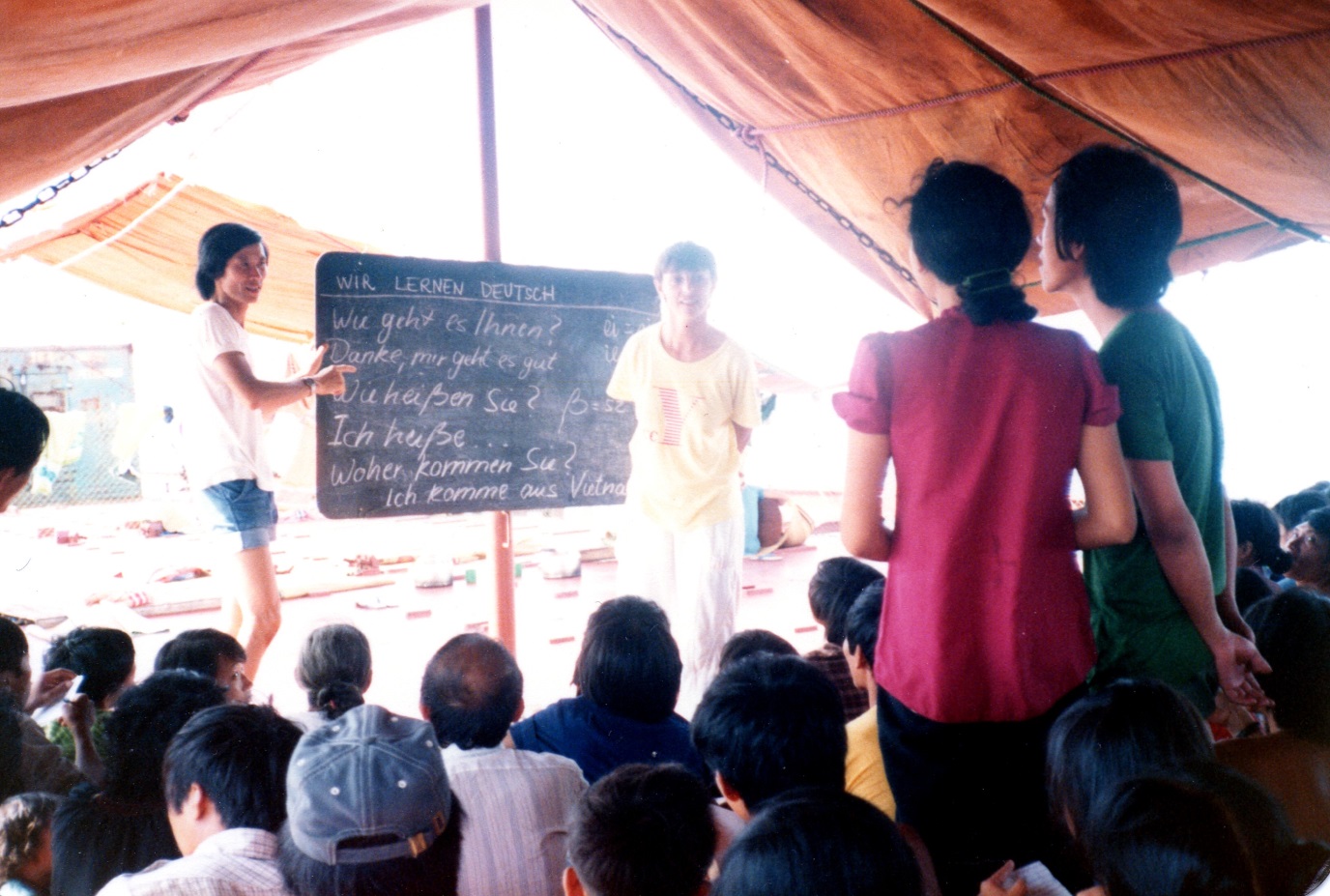

Because the 357 people were rescued by a German ship, owned by a German and docked at a German port, they were allowed to settle in Germany. All the provinces of Germany would share the cost of accepting and supporting them. None of the 357 refugees could understand or speak German. So to acquaint them with their new country, I spent a couple hours a day introducing them to life in Germany covering a variety of topics: traffic laws, social services, social insurance, employment, customs and traditions, weather, education system, banking, using a public phone, home heating system and even entertainment. I found so much pleasure in being able to share my knowledge with them. Three German language classes were organized on board. At first, they were very well attended. However, learning the language was a challenge to many, and as time went by, the number of students decreased rapidly.

In the meantime, the ship was braving the stormy Indian Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. As the high winds and tall waves hit the flanks of the ship swinging it from side to side, our people were rolling all over unable to control their sea sickness. Some couldn’t eat for 2 days. The lemons I brought to them helped calm them down. The stronger ones, however, kept preparing the food and dancing with the waves. I admired their resilience and determination to overcome all difficulties in their fight for freedom. It took 2 weeks to cross the Indian Ocean.

In August, 1986, the ship reached Somalia. Everybody tried to get a peek of the bare ridges under the scorching heat. The temperature was 43 degrees C when we crossed the Red Sea. On August 19, 1986 we saw the well-lit oil rigs of the United Arab Emirates from afar. The next day we arrived in the Suez Canal. The captain warned everyone that Egyptian vendors, customs and security officials and guides would be boarding the ship and that they should keep an eye on their belongings, including shoes and clothing. At the same time, all crew and Committee cabins were tightly locked. The Egyptians used ladders to board the ship. They set up an instant flea market selling fake products, including counterfeit US money. In the brouhaha of arguments, people kept laughing and enjoying themselves while some reporters were running after us taking pictures and interviewing non-stop. It was a challenge directing people where to go and translating for them, but I did it. A few days later “Die Zeit”, a prestigious German magazine featured 2 pages for the Vietnamese Boat People. “[…] a real story of compassion and it is understandable why Germany sent a ship to rescue the Vietnamese boat people in the South China Sea” it would read.

There, in the Suez Canal, Dr. Neudeck announced the good news to our people “the German government will receive you with open arms and warmly welcome all of you in Hamburg. We have lots of goodies for the children”. Tears of joy and gratitude flowed on their faces and the clapping joined force with the winds to push away the heat of the day. The raised arms looked like a bouquet of thanks sent to Germany via Dr. Neudeck and the reporters at Port Said, the last stop in the Suez Canal.

On August 22, the ship entered the Mediterranean Sea. The heat of Africa had dissipated. Escorted by a few seagulls in the sky and a school of sharks at the bow, the ship finally saw the coast of Italy from afar. As a parting gift, Captain Claus Heinrick gave everyone a tour of the ship, from the commanding post to the mechanic room, crew cabins, kitchen and dining room. I also invited everyone to join me in my cabin to listen to Vietnamese music and share a few cigarettes and cans of pop. It was certainly a relaxing and enjoyable day. In return, I was given some handcrafted paper flowers, beautiful souvenirs of the trip.

The ship headed north along the Portuguese coast, crossed France and docked at Doves, England. Finally, in the morning of September 5, 1986, it reached port Cuxhaven, Germany. Eight German immigration officers and policemen boarded the ship and completed the required paperwork. Reporters from Germany, the US and France were also busy at work. The refugees, who couldn’t sleep a wink the night before all came out to ask questions, confident that they had reached the land of freedom and human rights. Boxes of brand new clothing and shoes and gifts from Otto Versand Company and Lufthansa Airline were distributed to the newcomers. I was exhausted.

V. “Welcoming Arms”

On September 5, 1986, we reached Port Hamburg amidst the cheers and welcoming arms of hundreds of Germans and thousands of Vietnamese lining up along the Elbe in the Blankensee area. When I saw the tower of the Church of St. Michael in the middle of the port I broke down into tears sharing the happiness, love, and memories of the long journey of 4 months of people forced to abandon their country. The humanitarian mission of the CA II ended there, but the fight for our people would go on.

Up to 1986, the flow of refugees had slowed down, but the financial contributions by Germans to the Cap Anamur Committee never stopped. Dr. Neudeck’s constant lobbying and the support of people in Germany and Europe resulted in the creation of the Cap Anamur III a year later; a joint cooperation between the Cap Anamur Committee and the French humanitarian group, Médecins Du Monde. Cap Anamur III would also return to the South China Sea.

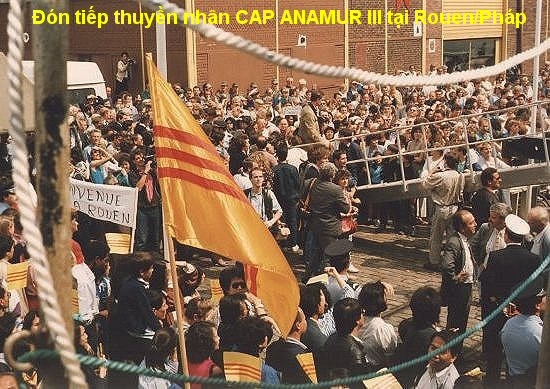

Médecins Du Monde was founded by Dr. Bernard Kouchner (Minister of Humanitarian Department later on, and Minister of Foreign Affairs of France from 2007 to 2010) and Dr. Alain Deloche, President of the group at the time. .The French Cap Anamur III (registered as ROSE SCHIAFFINO) made 3 trips and rescued 14 boats and 905 refugees from April, 1987 till June, 1987. During these trips, it was escorted and assisted by 4 French Navy ships. Dr. Nguyễn Ngọc Kỳ (former Air Force Major) and Dr. Đường Thiện Đồng (former Paratrooper Lt. Colonel), both of the U.S. SOS Boat People Committee, took turns assisting on each trip. When the Cap Anamur III returned to Rouen, France on August 21, 1987 all the refugees rescued were allowed to settle in France. Mr. Phan Lạc Tiếp (former Navy Captain, Vice President of the U.S. SOS Boat People Committee) was part of the welcoming group in Rouen.

1989 marked the beginning of a strict screening and forced repatriation policy imposed on Vietnamese refugees. At the same time free countries around the world also ended their settlement programs. In spite of all that, the mission of Cap Anamur Committee never ended, due to the fact that refugee boats were still spotted on the South China Sea. The Cap Anamur Committee brought to life two more ships, the Cap Anamur IV (June, 1989) and Cap Anamur V (October, 1989) with the mission to assist and protect refugees from the pirates and lead them to the refugee camps.

In total the ships of Cap Anamur Committee gave medical assistance to 35,000 refugees in the camps in Southeast Asia (Cap Anamur I), saved the lives of 11 300 people on 226 boats (the CAI, II, and III) , protected 500 people from pirates and escorted them safely to the camps (the CAIV and V). The Cap Anamur Committee, a private German humanitarian group, accomplished its noble mission and never faltered.

Nguyễn Hữu Huấn